The Humble Ovix and the Changes Wrought in Her Form - The Journal of Anther Strein

The Journal of Anther Strein

Observations from a Travelling Naturalist in a Fantasy World

Written by Lachlan Marnoch

with Illustrations by Nayoung Lee

25th of Lodda, 787 AoC

Western Fringe of Erefal Wood

The Humble Ovix and the Changes Wrought in Her Form

We have managed to dry off since I penned my last entry. Days free of the tyranny of the rowax, I find myself in a better mood – marred only by the fact that we have become somewhat lost. The twin causes of this, both at the hands of the river1, are the ruination of our maps and our displacement downstream. Damp as our belongings are, my outlook remains mostly undampened - between the two of us, particularly with Prentis’ innate directionality, I feel sure that we can scrape together a combined knowledge sufficient to get us back on track. If we wished to re-join our original path, we could have followed the river upstream again, but this would only have succeeded in placing us once more in the rowax’s territory - a stunt we wish to avoid. Instead we have struck north-west directly.

The river washed us to the lip of a shallow valley running parallel to the Crown Mountains, which now guide our way. This range cradles the Veduka Rainforest, and it is from its peaks that the Sunken and Veduka Rivers descend (along with many others). Although not our original plan, we need only to follow the range and we will eventually be back on track. The soil here, pressed up against the hard rock of the foothills, is thinner, and the erefal trees proportionately so. Although we have lost the path, our way is easier now. It also presents us with a stunning view of the Crowns, a series of stark ragged crags climbing into the sky. These mountains would have been visible from Leafshrine, had the trees not broken every possible line of sight, but now they veritably tower above us. We can even see the Top of the World – a mountain in this range famously crested by a single erefal tree. Not a particularly large specimen, it nonetheless raises the mountain’s summit by some hundreds of heights, and has done so throughout written history. How the tree came to sprout there is a mystery, but perhaps it was planted deliberately, or perhaps a seed was carried there by the wind. How it survives is even more mysterious, as the thin soil and cool air usually found at the mountaintops should not be sufficient for the sustenance of so great a tree – but an exception has clearly been made. Life often astounds in its resilience.

I fear that Prentis may now regret coming on this detour with me, although he is too polite to say so. He appears less comfortable than me in our current vague situation – although Austia love exploration dearly, they care little for being lost. I came upon him last night with forelimbs clasped and head bowed, in what can only be described as a prayer – and not a Febregonic one. He seemed startled and distraught to find me watching him and offered profuse apologies. Not finding myself deeply affronted by such blasphemies, I assured him that I would keep his secret, but my curiosity2 pushed me to inquire further. Prentis, although lacking the false condescending piety of a Taragos, has never struck me as the blasphemous sort.

After some light pestering, he confessed that he was asking the Waykeepers to guide our path. I was vaguely familiar with the myth of the Waykeepers but was curious about Prentis’ perspective. He was reluctant to share any details at first, but the more I assured him that I would not be turning him over to an Inquisition the more open he became.

The Waykeepers are a mythical group of Austia believed in widely by Prentis' kind. They are said to appear only when an Austium is lost3 or in grave danger, and to have a preternatural knowledge of all of Pendant’s hidden paths and passages. Prentis tells me that Austia will sometimes call on the Waykeepers, in a prayer-like4 fashion, to guide the path to safety. I had always regarded them as nothing more than an aspirational superstition, but Prentis seems to have some lingering belief in them. There are tales of the Waykeepers whisking away the inhabitants of castles under siege, and of plucking famous explorers from the jaws of starvation. They are fabled to have fomented the disappearance of an entire village from the western end of the continent and its reappearance at the eastern. There are even stories telling of a deep involvement with the rise and fall of the Austium Empire – a civilization which chiefly occupied the region now known as the Austium States but, until its collapse nearly three hundred years ago, had quite an abnormal reach. There is no widely-accepted historical explanation for the speed and ease with which the Empire seeded and coordinated its far-flung colonies. No doubt this has fed the Empire’s near-legendary reputation among the Austia, who have few such domineering legacies to point to. Little surprise then that its storied reign has become tied to the Waykeepers, as most events in Austium history seem in some way to be.

Prentis’ poor spirits may also be tied to the loss of a scent-artwork he had been composing for some time at Leafshrine. Unfortunately, it was quite ruined by our turn in the river. Outwardly, he bore the loss stoically, but the sag I have noted in his antennae since has betrayed his deep inner disappointment. Prentis has the same energy for this hobby as I pour into my living studies, so I quite sympathise. Had this journal been ruined, words could hardly have described my frustration.

The composition of scent-art, produced from the admixture of a variety of scents and intended for perception with antennae, is a common craft among Austia. Many of these scents are derived from plants, and Austium scent-artists usually tend private gardens of their own5. The art also includes a pheromonal component, by which a rich layered complexity can be achieved with their relative strengths and positioning. The artform’s subtleties are generally lost on non-Austia, myself included, but the most famous works, I am informed, have a sophisticated command of metaphor and social commentary. The completed pieces tend not to retain their character for long, scent being naturally ephemeral6 - but the loss of an incomplete artwork is nonetheless a blow to the spirit. I’ve tried to cheer Prentis by pointing out the fascinating features of the numerous flora and fauna by our way. Although more interested than most, he seems not quite to share my level of enthusiasm for the living world.

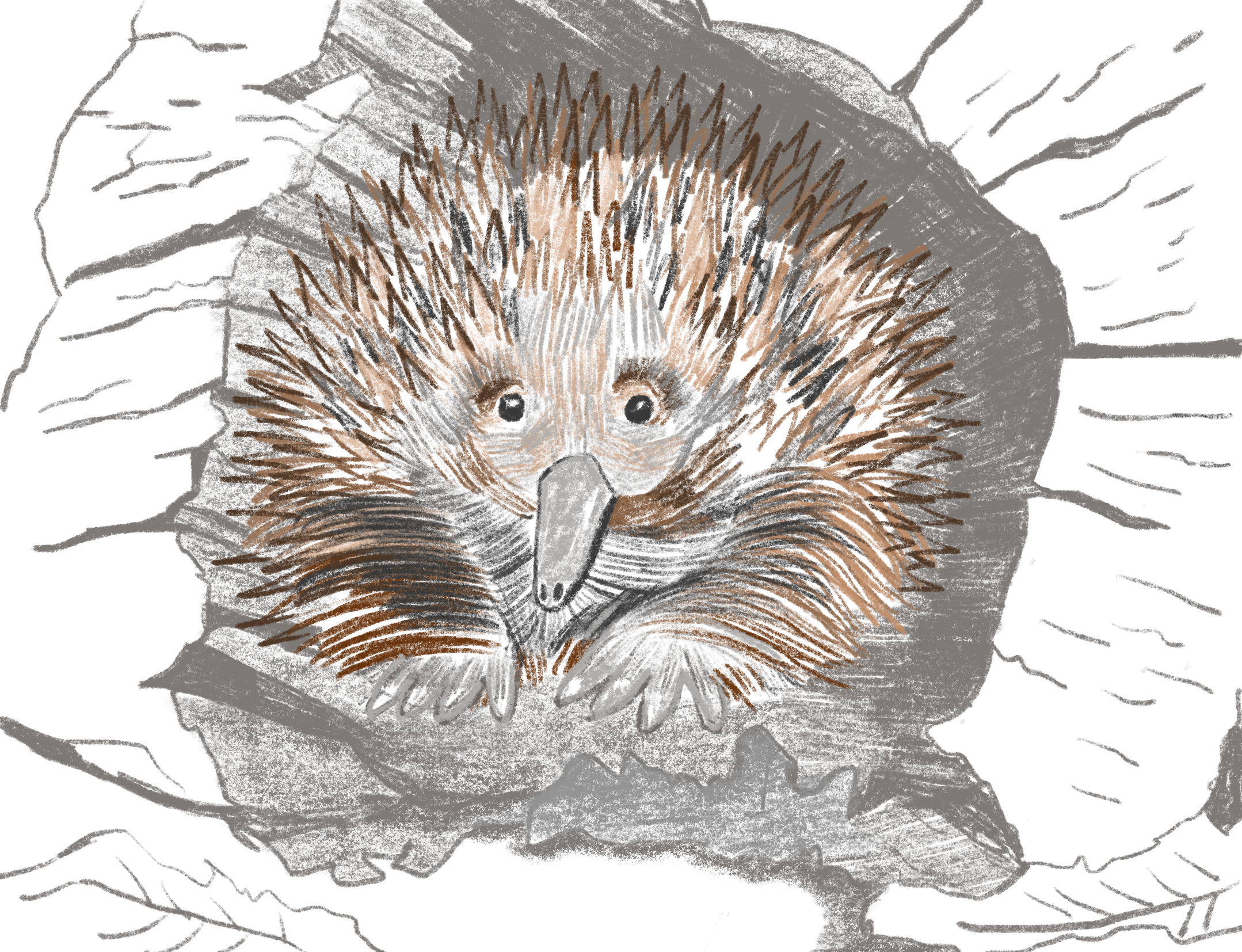

Today I came across a set of footprints belonging to a small animal. Quite naturally we followed them to their source, an Essichard echidna (Satallus essichardus) which was feasting happily on a nest of erefal termites (Geoinuippyeoleul ssibda). We watched him for some time - he exploited his strong claws to scrape the rotting log apart, and swept up prey up with expert flicks of his long, bright pink tongue. He paid no mind to the furious insects swarming about his eyes and nostrils. I tried to get a closer look, but the wind changed; he curled up into an adorable spiky ball and waited patiently for us to leave. We may have tested even his patience, for I couldn’t resist taking sketches and measurements.

Echidnas are monotremes, a group of mammals which also includes the platypodes and the rangforims. Unlike other mammals, monotremes reproduce by laying soft, leathery eggs7. This has been put to intensive use in another echidna species, the ovix. As a close relative of the Essichard species, this animal was pushed to the forefront of my mind by today’s encounter. This is not for the first time – I have been pondering the ovix, and its relationship to the echidna encountered today, since long before leaving Leafshrine8. It is high time I set these thoughts to paper.

The ovix echidna, usually just called the ovix, is farmed throughout Proesus9 for its meat, milk and eggs10. This has been happening for a very long time, far longer than any surviving record has existed. The ovix’s diet – somewhat expanded, depending on those keeping it – ordinarily consists of ants, termites, and the larvae of other insects. Many who keep ovices also keep an ant farm as feed. The most common choice is the friendly ant (Amicus utilis), a species which has itself been thoroughly domesticated. The ovix, as with other echidnas, deposits her egg directly into her pouch, but rejects it as soon as the next one is laid. She seems able to tell if an egg is fertilised, as she ceases laying while waiting for it to hatch. Egg farmers can either check the ovix’s pouch every morning or else collect the rejected eggs from the ground; the latter is easier but presents a greater risk of breakage. While the echidna lacks nipples, milk can be obtained from a brooding ovix with a specialised device, left attached to one of the two milk pores. This can be tedious, and has a small payoff compared to the milk of the gambuk (Veambarr kantamrgam abhayantara), which is both far more accessible and produced in greater amounts. Nonetheless, the relative ease of keeping a milk ovix keeps them in casual use, even where the much larger gambuk is favoured for commercial quantities.

I find domestic organisms deeply fascinating, for it is possible in them to perceive just how malleable life can be. Those who hew to the notion of a fixed set of unchangeable species (that is, most naturalists) find it difficult to explain the changes that can be wrought, in our tame creatures, by a determined breeder. The ovix is a prime example. Several breeds of ovix exist. There are those serving a special utility, such as a breed which lays larger eggs, one which produces a greater amount of milk, and one with a greater proportion of edible meat. But there are also many breeders – an industrious community of ovix-lovers - who experiment judiciously with the aesthetic qualities of the species. There are those used for show, with long, luxuriant spines and altered colouration, particularly in the spine-tips. There are those with longer or shorter snouts, or with furry claws. There are even those with altered behaviour, becoming friendly and affectionate. These are the breeds usually kept as pets, a practice becoming more popular. Although most ovices are tame in some degree, and certainly all a good deal more so than their timid cousins, these last are exceptionally so. Each of these races breeds true – that is, if an ovix is allowed only to procreate within its breed, it will produce only further members of that breed – and yet there is no difficulty in crossing to produce half-breeds.

It is not considered any great controversy, by breeders of domestic animals, that change can be effected in a stock by careful selection of mating partners. Naturalists, however, seem either ignorant of the phenomenon or loathe to admit it to their general thinking. Those who do recognise it generally assume that the traits extracted from these hapless creatures were previously hiding latent, in the 'pattern' of the species; breeding, in this view, simply calls them forth. I do not believe this to be the case. There is real change going on here, I am sure of it. Most of these breeds have traits previously unseen in any ovix, and unknown in any wild echidna. New breeds can be produced within quite a short span by a dedicated, and lucky, breeder - I can list three which seem to have been produced in the last century. It seems certain to me that these breeds have changed, diverged, over their generations of selective breeding, and that this has been caused by the actions of those performing the breeding.

Variation of traits within a species occurs throughout nature; no two wild echidnas are identical to a careful eye, just as no two Paluchard have the same face. If a being’s traits can be inherited from its parents, as few will contest, then allowing only those with a desired trait to breed must tend to propagate that trait. If that trait should at any point become enhanced by random chance, a breeder might readily seize on it and propagate it further. For example: it seems reasonable to me that an ovix with a slightly shorter than normal snout, but still within the normal variation of its species, might occur - and that a breeder, for some reason finding the notion of a shorter snout appealing11, would hence select this ovix to be bred. He might even select, for its partner, another ovix with a snout shorter than the average. Some of the offspring would then be likely to inherit a short snout. By continuing to select those with short snouts for breeding together, this trait can be propagated to many members of the species. And what, then, if another variation occurs from this promulgation - one with an even shorter snout? Would not the breeder favour this one for further breeding, thus shortening the breed’s snout further? And by continuing to do so over many generations, and if fortunate in the occurrence of the desired variations, might not he succeed in almost eliminating the snout entirely? I suspect that this is precisely how the short-snouted ovix breed has come to be. This does require that new, minor variations on the 'pattern' of a species can occur spontaneously, perhaps at random, but I think this no problem at all considering the breadth of previously unknown traits drawn out by domestic breeders. The actual, fundamental cause of these variations, I do not pretend to understand – although I do have some ideas.

An instantaneous creationist, such as those found within the mainstream Order of Febregon, might argue that the ovix was created, as it is, expressly to serve sapient beings, without any need for a wild ancestor. They might even fold the apparent pliability of the animal’s appearance and behaviour into this purpose, claiming that this, too, was a gift from the Creator to us. I do not think that such things occur in nature12. I believe that Febregon’s plan is one of increments.

I have constructed something of a straw man in the above, for there are few outside the Order of Febregon who refute any change or variation in species whatsoever. Indeed, many naturalists write that it is likely all domestic species descend from a wild form, and have undergone changes throughout captivity - even if they will not fully admit the true novelty and extent of the changes. Thus, a hunt has been undertaken for the wild counterparts of many of our ancient farm animals. It has sometimes been successful, but is not always straightforward.

Although several echidna species exist, scattered across Proesus and its neighbouring islands, only one appears to have been domesticated to result in the ovix. Precisely which has been a subject of some mystery. Until recently it was widely believed that, in the time since domestication, the wild ovix ancestor had gone quietly extinct – a fate which has certainly befallen the wild gambuk (Veambarr kantamrgam preajenirrar). Despite confoundment by a lack of fossils resembling the ovix, one can see how this conclusion might be drawn: the domestic ovix is, on average, three times the weight of even the largest wild echidna. Even the unspecialised breeds lay an unfertilised egg (proportionately large), as frequently as once per day throughout the entire year13, and produce volumes of milk orders of magnitude beyond wild species.

It once seemed certain that the wild predecessor of the ovix must share these traits, and since no such animal was known it was considered to have vanished. The Essichard echidna, the only wild species to produce unfertilised eggs, was thought to be a mere relative. However, the two have recently been found able to freely interbreed, which no other two echidna species can do. This places, in current definitions, the ovix and the Essichard echidna in the very same species. To this end, I hold with the view (shared by several noted naturalists) that the ovix - currently Satallus ovix - should be reclassified as Satallus essichardus ovix, a subspecies. This would also make the Essichard echidna the only viable candidate for the ovix’s wild ancestor.

If this is true, and I have become certain that it is, the changes effected since the ancient domestication event are quite extraordinary. I have already mentioned these differences, but summarising again: compared to its wild cousin, the ovix is significantly larger, with a greater proportion of muscle, and produces far more milk. It also has shorter and duller spines, lays larger eggs every day, and behaves quite differently – instead of curling up in fear of a person’s approach, like the specimen we met today did, an ovix is more likely to approach her in search of food.

Each of these changes seems suspiciously beneficial to the ovix’s sapient masters – either in allowing it to be handled safely or in causing it to produce greater quantities of food. I am hardly the first to take notice of this fact, of course, which seems to go as a general rule for domesticated species. Some naturalists have even gone so far as to suggest that it is the will of the farmer itself causing the changes - that the materials of life are slowly, as if by psychic connection, obeying the wishes of the sapients that make use of them. They are not so far from the truth, I think, in terms of the ultimate cause, but there is nothing mystical to it. A gradual accumulation of small changes, under the watchful14 eyes of sapient masters, is sufficient to explain it. I have already detailed how new breeds can be created in this manner – why not, over a greater span of time, a new subspecies? Or even – and this is where we venture toward the scandalous – a new species?

The more I ponder this question, the more certain I become that the ovix has descended from a wild ancestor, almost certainly Satallus essichardus, and has diverged gradually in the care of sapient hands. There is no doubt in my mind that the changes effected in the humble ovix have come about due to the will of its captors. Nor do I think these changes atypical of a long-domesticated species – I shall have to, at some juncture, make closer note of the grubdog, the elari, the friendly ant, the ipis and the domestic wobali, all of whom have been transformed significantly from their native forms.

Although the significant disparity between the ovix and its wild ancestor has caused the scratching of many heads, it fits extraordinarily well into the principles that are steadily growing in my mind. In fact, it fits almost too neatly into my ideas on the origins of species.

Prentis, while I have been writing this, has begun composing a new scent-artwork. At its base is a crumbled erefal leaf and a piece of dry wood disturbed by the echidna – rich, he says, with the panic-pheromones of the termites. He seems to have reclaimed some of his morale already! He is asking after the scents of the flowers in Veduka, looking forward to adding them to his composition. I, too, anticipate seeing and smelling these flowers with excitement – the memory of such scents is a powerful bond to my childhood. Soon, Febregon willing! Or perhaps I should invoke the Waykeepers instead.

1 Which, in my mind at least, has been retitled to Rowax Chase.

2 Rivalling that of the rowax that, in recent memory, we so narrowly escaped.

3 A rare event, to be sure.

4 Prentis insists that it is not prayer, but I was unable to translate the word he used, and I can think of no other name for it.

5 These gardens sometimes reach the status of artwork in themselves, both visually and olfactorily.

6 Some academics see the ephemeral nature of the medium as central to its beauty. A quote from the famed scent-artist Jonquin Tentis goes something like this: ‘Permanence is for knowledge, transience is for art.’

7 Some argument has gone into whether they can truly be called mammals, paralleling the debate of whether the essiloth deserve to be numbered among the reptiles. The essiloth, with their warm blood, occasional feathers, and elevated metabolism, have a better case for secession from their class; monotremes, on the other hand, share all the important characteristics of a mammal but for the ability to give live birth. To my mind they must be labelled merely as exceptional mammals.

8 The stock of ovix meat we carry and have been consuming (furtively, in my case), and its source in the pens of Leafshrine, is partially responsible for maintaining the species' place in my mind.

9 And beyond – the colonists making for the Old World would have taken many of the useful animals with them, I imagine, and trade may have spread it far and wide besides.

10 The spines also have a variety of uses, sometimes given out as toothpicks or used as skewers for the animal’s own meat. This latter practice seems vaguely distasteful to me, but I can’t quite articulate why.

11 I only said that these breeders were successful, never that they were rational.

12 Nor, strictly speaking, has the ovix, as we shall now see.

13 No wild echidna lays more than once a month, and most only in a specific season.

14 Or even unwatchful – by preserving best those animals most useful to the farmer, might he not inadvertently shape his stock, in the same slow fashion, to become more useful?

Photo by Jacob Dyer