The Austia of Leafshrine - The Journal of Anther Strein

The Journal of Anther Strein

Observations from a Travelling Naturalist in a Fantasy World

Written by Lachlan Marnoch

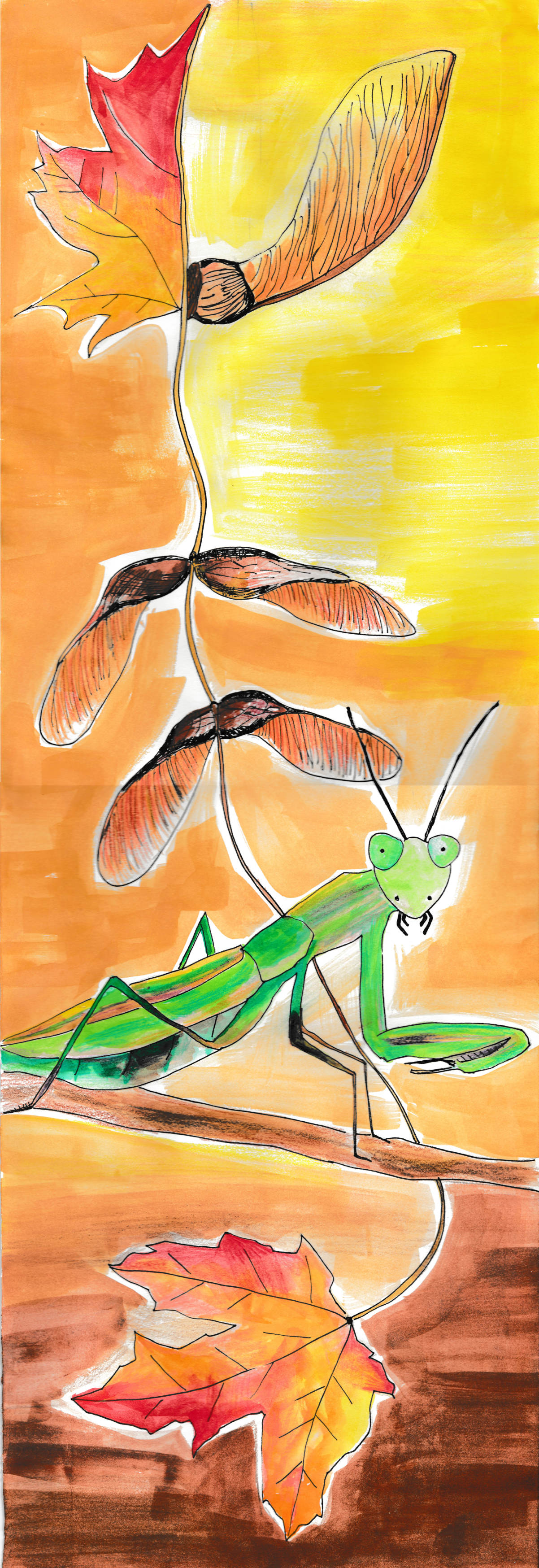

with Illustrations by Nayoung Lee

Previous: Foreword

18th of Lodda, 787 AoC

Leafshrine Village, Erefal Wood

The Austia of Leafshrine

It has been some time since I wrote in a journal. I brought this little one - a fresh purchase - along with me when I left for this mission, with the express intent of writing in it every day1. This appears not to have happened - this is the first ink to stain these pages, my teaching notes and jotted observations having been directed elsewhere. I would excuse myself with the busyness of my schedule, but in honesty it has simply been difficult to find the motivation. I'm sure any writer will agree with me that the blank page always seems an insurmountable difficulty; but almost as soon as the first sentence is laid out, it is difficult for one to stop; and once the momentum of a schedule has been established, one looks upon the hesitation of the past self as nothing short of utter foolishness. Oh well. It is better to begin late than to never begin at all, I’ve heard they say in Baiikhan.

This is my last week in the village of Leafshrine, a tiny community of Austia (Teensies explorator) deep in the Erefal Woods. I was assigned here, along with a handful of other missionaries, to spread the light of Febregon to those who have forgotten it. The Leafshriners certainly fall into this category. They subscribe to a pagan faith known broadly as Verdanism, which involves the worship of plants. Their particular doctrine is a peculiar one in a number of ways, and one most exasperating to our dear Priest Taragos. I may expand on this later.

My duties here have not been clerical – I am, of course, not authorised for such things. Only males may join the Order proper, as is, quite naturally, Febregon’s will2. Although I am thus barred from participating in sermons, there has been plenty for me to do. Febregonic missions generally take a two-pronged approach to illumination – exhortation and elevation. Priest Taragos has undertaken the former, instructing the Austia on the correct manner of worship3. My duty lies in the latter, particularly with education. By elevating the way of life of primitive peoples such as this, we may show them the rewards afforded those dutiful to Febregon4.

The settlement itself seems to consist in large part of escaped slaves - most likely owned at one point by people of my own species. Shamefully, this has not been an uncommon fate for Austia in the last centuries, especially on the Essichard subcontinent. This village technically falls under the dominion of a minor Paluchard prince, although I have yet to see a tax collector here. The village is remote enough, and with little enough to offer, that most likely the prince has never thought it worth his time.

Although I have worked with Austia before, I have never spent so prolonged a period living among them. Austia are probably the least studied of the sapient species; it may well do to make a few remarks on them here, particularly on the people of this village. This will also serve to sharpen my skills of scientific scrutiny, bluntened by a period of disuse. I have been lax in recording my observations since embarking on this mission – my notes on the living things here have, thus far, been limited to a few scribbled points. My former professors would be most aggrieved. I feel, now that I may be about to leave, that I should commit them more formally to paper, lest any crucial detail be forgotten. I also feel that entering this habit now, before I embark on my upcoming journey, will put me in good stead for the variety of wildlife I am sure to encounter.

Austia do not breathe through their mouths, instead absorbing air through the spiracles that dot their body. Because of this, they do not speak in the same manner as the other sapient species. Instead, they communicate with several different sounds produced by various body-parts and with various means, including with air pushed through the spiracles, rubbed limbs, mouthparts clicked against each other5. Austia are thus physically incapable of speaking Proesine, which requires a larynx or syrinx to vocalise. Likewise, those of us with the necessary organs for Proesine are incapable of reproducing the clicks, pops, hisses and chitters of which Austium communication consists6. Although Austia can learn to understand our languages, and we can learn to understand theirs, it is much harder for either party than to learn a new language in our respective modes of communication. This has presented difficulties, both historically and in our current situation.

The remoteness of this settlement has resulted in a distinct lack of fluency in Proesine. The Order foresaw this and was kind enough to include an Austium Deacon on our mission. His name is Prentis7, and I’ve found him a most agreeable fellow. The language the villagers speak bears some resemblance to Central, the lingua franca of the Austium States with which I am passingly familiar, so with Prentis’ help over the past year I have been able to approximate a comprehension of the Leafshriner tongue8. Prentis found no difficulty in learning it, and was chatting fluyently with the villagers within weeks. A handful of the villagers also understand Swamplander9, my own language of birth; paired with our efforts at translating their speech, this has enabled a limited understanding to form between the villagers and the mission. We have also been teaching them to read and write, a skill previously absent here. Taragos still comprehends not a syllable of the Leafshriner language, nor of Central10, usually expecting me to act as interpreter for both the Leafshriners and for Prentis. He seems loathe even to communicate in Proesine, preferring the dialect of Essilorethan common to his home region.

The Austia as a species have endured discrimination for as far back as history goes. Although I rank lower than him in the Order hierarchy, I am often treated more politely11 by Taragos than Prentis, and I also noted that he was disfavoured compared to the other Deacon (a Paluchard, like me) who was12 a part of this mission. I have also observed that very few Austia, no matter their devotion, ever move beyond the rank of Priest in the Order. Perhaps such circumstances have to do with why these people have chosen to live here in such isolation. In addition to the slavery, that is.

The chief reason for these biases – seen most prominently in the slurs used against them, of which ‘cockroach’ is a prime example – appears to me to be their insect-like nature. Most of the other sapient peoples retain a general, instinctive revulsion for insects and other invertebrates13. I have no doubt this is the reason for the deficit in the study of Austia – let it never be said that there are no bigots among scientists.

Austia do exhibit several insectoid features, including six legs and a body plan in three segments - a squat abdomen, elongated throax, and round head. Current taxonomy suggests, however, that they are not true insects, but closely related arthropods of the class Oxydolus. Members of this class share the capability of absorbing extra oxygen, using a magical property of their blood - which, like that of insects, is coloured blue-green14. This ability enables them to grow to much greater (and more startling) sizes than other invertebrates, whose oxygenation capabilities are less efficient. Oxydolus is not the only group of invertebrates possessing this trait, but it is the only one in which it is basal to the class – that is, in which all members demonstrate it to some degree. The familiar grubdog (Vermis canis) and the dreaded glasp (Raptorus amethystus) number among this group, each also possessing six legs.

In the Austia, all six of these legs are used for walking, especially when speed is required. They can, however, stand on the rear four alone, raising the long thorax to a more upright angle, and the head perched at its tip to a higher position. This enables the use of the forelimbs, each of which terminate in two pairs of opposable pincers, for manual tasks; they can be used in conjunction with the mouthparts, including two pairs of palps, with which they are more dextrous. I hadn’t ever observed this latter behaviour until arriving here. I suspect this is because Austia used to the society of other species15 avoid using their mouthparts, having learnt that most non-Austia react to the habit with revulsion. I confess to finding it somewhat alarming at first, but I have grown used to it.

Austia are a good deal stronger than their spindly limbs betray, and light besides. Their claws are as skilled at finding purchase as those of insects. These combined traits enable Austia to climb surfaces as vertical as the trunk of an erefal tree, which has put them in good stead in this environment. Should they fall – and from the heights attainable in this Wood, such a fall could easily prove deadly – they can make use of their wings, which usually lie hidden below the hard carapace covering the abdomen. Austia, unlike Nuntia, cannot fly outright, but may use their wings to extend jumps and slow descents. Although not used in routine communication, I have seen Austia buzz their wings when frightened or engaged in aggressive confrontation - presumably, and perhaps unconsciously, in an effort to appear larger. They do well to make use of this illusion, for Austia are indeed smaller than other sapients. When upright, they usually come to less than a halfheightA, just above the waist of your average Essilor.

The Austia of Leafshrine are mostly of a green-brown colouration. This is a race common to this region, but other phenotypes are represented here as well. Morphs found in Proesus range from deepest black, to a handsome bronze, to a bright green. Some of the bronze morph might even be described as golden, and one such individual appears here.

Although the hearing of an Austium is generally good, and the sense of smell exceptional, they have relatively poor eyesight. I suspect this is linked to the compound structure of their eyes, being composed of hundreds of tiny units (ommatidia) – the sensitivity of which seems lacking. However, although they appear unable to resolve individual objects well, I believe they can perceive rapid motion with much greater acuity than my own eyes. They can also see backward with little effort, afforded a much wider viewing angle than forward-fixed eyes. This is of use, for the eyes cannot be rotated independently of the head. The alignment of the ommatidia is such that those viewed head-on appear black, while those neighboring units, viewed at an angle, appear brown or green. This results in the illusion of a pupil at the centre of the eye, which appears to be pointed in the direction of the observer no matter where the Austium's attention is truly directed. This is a most eerie phenomenon for those of us used to reading social cues from true pupils. Austia are not naturally in the habit of turning to face those they are addressing, presumably because body and facial language play a negligible role in their usual communication. To appear polite, those in frequent contact with other species often have to force themselves into the practice. Picking up on non-verbal cues is a great strain to them, even more so than the various differences in body language between the other sapient species.

As I have mentioned, their sense of smell is most acute, apparently delivered to them by means of the pair of great, waving antennae perched atop their heads. These antennae are in a state of constant, and likely involuntary, motion, sweeping independently this way and that in a manner that I find most entrancing (and at times distracting) to watch. They are also capable of being regrown if broken – which is fortunate, for they are quite delicate. Each of an Austium’s limbs can be regenerated, albeit only while the Austium is young and growing quickly. Prentis tells me the antennae can be regrown at any time, with the process merely being quicker in the pre-adult phases. He himself is currently sporting a slightly lopsided pair, one having been lost in Forum to a prematurely slammed door.

When asked, any Austium can give you the direction of magnetic north, as unerringly as my own compass. The organ responsible for this remains unknown – little surprise, as the magnetic phenomenon itself is still a mystery those who study it, although other animals have also exhibited sensitivity to the magnetism of Pendant. They make good use of this extra sense, and have a reputation as excellent explorers and navigators. Austia rarely seem content with blank spaces on a map, and are driven to explore every corner of the environment in which they live. This is the origin of the second half of their binomial, Teensies explorator. Many a detailed map of the surrounding forest can be found painted on to the trees at Leafshrine. Austia, like all of the sapient species, can adapt to almost any climate, and settlements can be found in a vast range of conditions. However, they show a preference for warm, humid environments and low altitudes.

The Austium diet is deeply varied, and they seem able to subsist on almost any food. This makes them most survivable indeed - they are capable of eating meat at any stage of decomposition without any apparent consequence. Perhaps compensating for this is the shortness of their life expectation, a mere thirty to forty years even in the most comfortable conditions. This lifespan begins with a long, thin egg, laid in clutches of dozens16. Only a small fraction of these hatch, after a period of no more than a few weeks, and those unsuccessful in doing so are swiftly and instinctively set upon by the infants in their first feeding. I first bore witness to this after coming here, although I had read about it in my textbooks. Although this might seem barbaric to some, the eggs that are eaten are unfertilised duds, or so I understand, provided for the express purpose of feeding those few who have hatched. The new-borns seem able to distinguish the infertile from the fertile, probably by scent. I noted two of them pass over an unhatched egg which I believed at the time to be a dud, but which soon split forth into a latecomer.

From there the Austium children grow swiftly. Those offspring resulting from the clutch which I witnessed are already able to compose primitive sentences, at a mere seven months old17. Rapid growth and learning are encouraged by the care of the parents, who typically share an equal role in the parental responsibilities18. After five to six years the Austium leaves this phase of rapid growth and is considered to have reached adulthood, but continues to increase gradually in size until the day of their death.

Although this is my first entry written from Leafshrine, it may well be my last. We have just today received a letter from the Order of Febregon instructing us to return to Forum at our soonest convenience. I do not feel that our work here is complete. I am not, in truth, overly concerned with the fidelity with which the people of Leafshrine worship Febregon – I decided long ago that the beliefs of others are not my concern. But Prentis and I have been doing good work on raising the standard of living in the village, work which I now fear will never be complete.

Nonetheless, my mind has turned to the possibilities ahead. As torn as I am by this ending, I must confess to finding myself most enervated by the thought of travelling once again. I am also impatient to catch up on my reading – I have been unable to receive my journal subscriptions here, and I could easily have missed a great discovery or two in the natural sciences. For now, I must sleep. The Leafshriners do not tolerate flames of any sort, and I could not afford a mage-lamp (such as the one adorning Taragos’ quarters) to bring along. It has thus been a year of sleeping when Sororius does19 - I write these very words with the last reminders of her daylight. Good night!

1 The purchase may also have been influenced by the pleasant compactness of the book, and my own weakness for charming stationary.

2 Oddly enough, I can locate no passage attesting this in the Book of Dreams, and the one time I called upon a priest to point one out to me he became instantaneously flustered. But the Order is, of course, unfailing in its interpretation of Febregon’s word, and could never make such a fundamental mistake because of baseless cultural assumption.

Oh dear. One entry in and I have already flirted with heresies. Note to self: burn journal.

3 His success has been, to put it generously, mixed.

4 Such is the Order’s reasoning. It often works, but it relies on a certain logical leap in which the new comforts experienced by the converted people are linked to worship of Febregon. This is, demonstrably, a fallacy, as one only need travel to Aranta, the Fork or even Manifold to demonstrate. In these regions the people enjoy a life as free of poverty as any in the Febregonic world (more so than many), and the Order has nought but a toehold. One might, if one was feeling ungenerous, even accuse the Order of exploiting the poverty and ignorance of locales such as this in order to accrue new believers, rather than for charitable purposes. One might also find oneself the subject of an Inquisitorial Hearing for saying so out loud.

5 Prentis informs me there is also a component carried by scent, which lends the kind of emotional nuance found in the tone of voice in Paluchard and Essilor. My nose is not sensitive enough to catch the scents they emit; I thus find it very hard to tell when an Austium is being sarcastic, and as a result often find myself at the butt of Prentis’ teasing.

6 I am told Nuntia are the exception – I hope eventually to observe firsthand their remarkable talents at vocal mimicry, but there are not many in Forum or in the locales in which I have served the Order. Those few which I have encountered, I have been too shy to ask for a demonstration.

7 He had to write it down before I understood it. Transliteration of Austium syllables is non-trivial.

8 To use this synonym is especially inaccurate here, as Austia lack tongues.

9 This, to my deepest shame, only lends further credence to my ‘former slave’ hypothesis. The Swampland Kingdom remains foremost in Proesus in its condonement of, and benefit from, slavery. This is not a badge to be worn with pride, but I fear there are many in my homeland who still do so. The inhabitants here have been exceptionally hospitable, considering.

10 I have heard him use, on more than one occasion and in connection with both languages, the word ‘barbaric’.

11 This is saying something, as his composure toward females in general, even those of his own species, is far from respectful.

12 The use of past tense here, I will endeavour to explain in another entry.

13 This is not mentioned here to excuse such bigotry, but rather to push it to the fore of one’s mind. Although similar instincts exist in all of us, they are contrary to Febregonic values and must be resisted if we are to exist in true society. Such things cannot be fought until they are acknowledged.

14 Alchemists have recently found the reason for the differences in colour – where vertebrate blood contains large concentrations of iron, rendering it red, most invertebrate blood (more correctly called haemolymph, I understand) contains copper instead. This is now believed to be linked to the intrinsic differences in oxygenation capacity (that is, before magic becomes involved), although the alchemists are still puzzling this out.

15 Several of my colleagues would use the word ‘civilized Austia’ as shorthand here, but I refrain from this. I find it a deeply biased assumption that Austia cannot be civilized without ‘help’ from another (and here I have refrained again from using ‘higher’, the preferred term of my old anthropology lecturer) species – their civilization is simply of a different nature.

16This manner of reproduction is chiefly responsible, I believe, for the inaccurate stereotype of Austia ‘breeding out of control’, a specist anxiety commonly held in mixed societies and stoked by conservative newsprints. In reality, these clutches are not laid any more than twice per decade, and the proportion of eggs that become viable offspring is quite small. Because of this, Austia have a rate of population increase no greater than my own species, and possibly less than that of Essilor.

17 They are quite adorable, and Prentis and I never miss a chance to play with them. I have grown deeply fond of them, especially the late hatcher (whose name is transliterated as Requit). She and her siblings will be the feature of this village I miss the most.

18 This, more than any of the Leafshriners’ various blasphemies and poverties, seemed most to offend Taragos. ‘Raising of children is women’s work!’, he has frequently scoffed. This has failed to raise him any further in my esteem. His surprise also betrays that, like me, he has not spent much time among Austia – Prentis informs me that this is not at all unique to Leafshrine.

19 Although Austia are nocturnal by nature (a trait which has occasionally earned them the unfair and ignorant label of 'lazy' among the bigoted), the inhabitants of Leafshrine have pulled their habits into a more diurnal cycle - which I was only too happy to match. If I may slip into the role of amateur anthropologist for a moment, I might suppose that this is in imitation of the plantlife they revere, much of which can be observed turning its face to the suns.

A 1 height is approximately equal to 2.13 metres or 6.99 feet.